Estimating diagnostic classification models

Source:vignettes/articles/model-estimation.Rmd

model-estimation.RmdIn this article, we will walk you through the steps for estimating diagnostic classification models (DCMs; also known as cognitive diagnostic models [CDMs]) using measr. We start with the data to analyze, understand how to specify a DCM to estimate, and learn how to customize the model estimation process (e.g., prior distributions).

To use the code in this article, you will need to install and load the measr package.

Example Data

To demonstrate the model estimation functionality of measr, we’ll examine a simulated data set. This data set contains 2,000 respondents and 20 items that measure a total of 4 attributes, but no item measures more than 2 attributes. The data was generated from the loglinear cognitive diagnostic model (LCDM), which is a general model that subsumes many other DCM subtypes (Henson et al., 2009). By using a simulated data set, we can compare the parameter estimates from measr to the true data generating parameters.

library(tidyverse)

sim_data <- read_rds("data/simulated-data.rds")

sim_data$data

#> # A tibble: 2,000 × 21

#> resp_id A1 A2 A3 A4 A5 A6 A7 A8 A9 A10

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

#> 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

#> 3 3 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1

#> 4 4 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

#> 5 5 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0

#> 6 6 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0

#> 7 7 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

#> 8 8 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

#> 9 9 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0

#> 10 10 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1

#> # ℹ 1,990 more rows

#> # ℹ 10 more variables: A11 <int>, A12 <int>, A13 <int>, A14 <int>,

#> # A15 <int>, A16 <int>, A17 <int>, A18 <int>, A19 <int>, A20 <int>

sim_data$q_matrix

#> # A tibble: 20 × 5

#> item_id att1 att2 att3 att4

#> <chr> <int> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 A1 0 1 0 1

#> 2 A2 0 0 1 1

#> 3 A3 1 1 0 0

#> 4 A4 1 0 0 0

#> 5 A5 1 0 0 1

#> 6 A6 0 1 0 0

#> 7 A7 1 0 0 0

#> 8 A8 0 1 0 1

#> 9 A9 0 1 0 1

#> 10 A10 1 0 0 1

#> 11 A11 1 0 0 1

#> 12 A12 0 0 1 1

#> 13 A13 0 0 1 1

#> 14 A14 0 0 1 0

#> 15 A15 0 1 0 1

#> 16 A16 0 1 0 0

#> 17 A17 0 0 0 1

#> 18 A18 1 0 1 0

#> 19 A19 0 1 0 1

#> 20 A20 0 0 0 1Specifying a DCM for Estimation

In measr, DCMs are specified and estimated using the

measr_dcm() function. We’ll start by estimating a loglinear

cognitive diagnostic model (LCDM). The LCDM is a general DCM that

subsumes many other DCM subtypes (Henson et al., 2009).

First, we specify the data (data) and the Q-matrix

(qmatrix) that should be used to estimate the model. Note

that these are the only required arguments to the

measr_dcm() function. If no other arguments are provided,

sensible defaults (described below) will take care of the rest of the

specification and estimation. Next, we can specify which columns, if

any, in our data and qmatrix contain

respondent identifiers and item identifiers in, respectively. If one or

more of these variables are not present in the data, these arguments can

be omitted, and measr will assign identifiers based on the row number

(i.e., row 1 in qmatrix becomes item 1). We can then

specify the type of DCM we want to estimate. The current options are

"lcdm" (the default) "dina", and

"dino" (see Estimating Other DCM

Sub-Types below).

You also have the option to choose which estimation engine to use,

via the "backend" argument. The default backend is

backend = "rstan", which will use the rstan package to estimate the

model. Alternatively, you can use the cmdstanr package to estimate

the model by specifying backend = "cmdstanr". The cmdstanr

package works by using a local installation of Stan to estimate the

models, rather than the version that is pre-compiled in rstan. Once a

backend has been chosen, we can supply additional arguments to those

specific estimating functions. In the example below, I specify 500

warm-up iterations per chain, 500 post-warm-up iterations per chain, and

4 cores to run the chains in parallel. The full set up options available

for rstan and cmdstanr can be found by looking at the help pages for

rstan::sampling() and

cmdstanr::`model-method-sample`, respectively.

Finally, because estimating these models can be time intensive, you

can specify a file. If a file is specified, an R object of

the fitted model will be automatically saved to the specified file. If

the specified file already exists, then the fitted model

will be read back into R, eliminating the need to re-estimate the

model.

lcdm <- measr_dcm(data = sim_data$data, qmatrix = sim_data$q_matrix,

resp_id = "resp_id", item_id = "item_id",

type = "lcdm", method = "mcmc", backend = "cmdstanr",

iter_warmup = 1000, iter_sampling = 500,

chains = 4, parallel_chains = 4,

file = "fits/sim-lcdm")Examining Parameter Estimates

Now that we’ve estimated a model, let’s compare our parameter

estimates to the true values used to generate the data. We can start be

looking at our estimates using measr_extract(). This

function extracts different aspects of a model estimated with measr.

Here, the estimate column reports estimated value for each

parameter and a measure of the associated error (i.e., the standard

deviation of the posterior distribution). For example, item A1 measures

two attributes and therefore has four parameters:

- An intercept, which represents the log-odds of providing a correct

response for a respondent who is proficient in neither of the attributes

this item measures (i.e.,

att2andatt4). - A main effect for the second attribute, which represents the increase in the log-odds of providing a correct response for a respondent who is proficient in that attribute.

- A main effect for the fourth attribute, which represents the increase in the log-odds of providing a correct response for a respondent who is proficient in that attribute.

- An interaction between the second and fourth attributes, which is the change in the log-odds for a respondent who is proficient in both attributes.

item_parameters <- measr_extract(lcdm, what = "item_param")

item_parameters

#> # A tibble: 66 × 5

#> item_id class attributes coef estimate

#> <fct> <chr> <chr> <glue> <rvar[1d]>

#> 1 A1 intercept NA l1_0 -0.98 ± 0.098

#> 2 A1 maineffect att2 l1_12 2.46 ± 0.158

#> 3 A1 maineffect att4 l1_14 4.46 ± 0.314

#> 4 A1 interaction att2__att4 l1_224 0.15 ± 1.331

#> 5 A2 intercept NA l2_0 -2.40 ± 0.301

#> 6 A2 maineffect att3 l2_13 3.99 ± 0.323

#> 7 A2 maineffect att4 l2_14 3.81 ± 0.339

#> 8 A2 interaction att3__att4 l2_234 -3.58 ± 0.381

#> 9 A3 intercept NA l3_0 -2.01 ± 0.160

#> 10 A3 maineffect att1 l3_11 2.22 ± 0.195

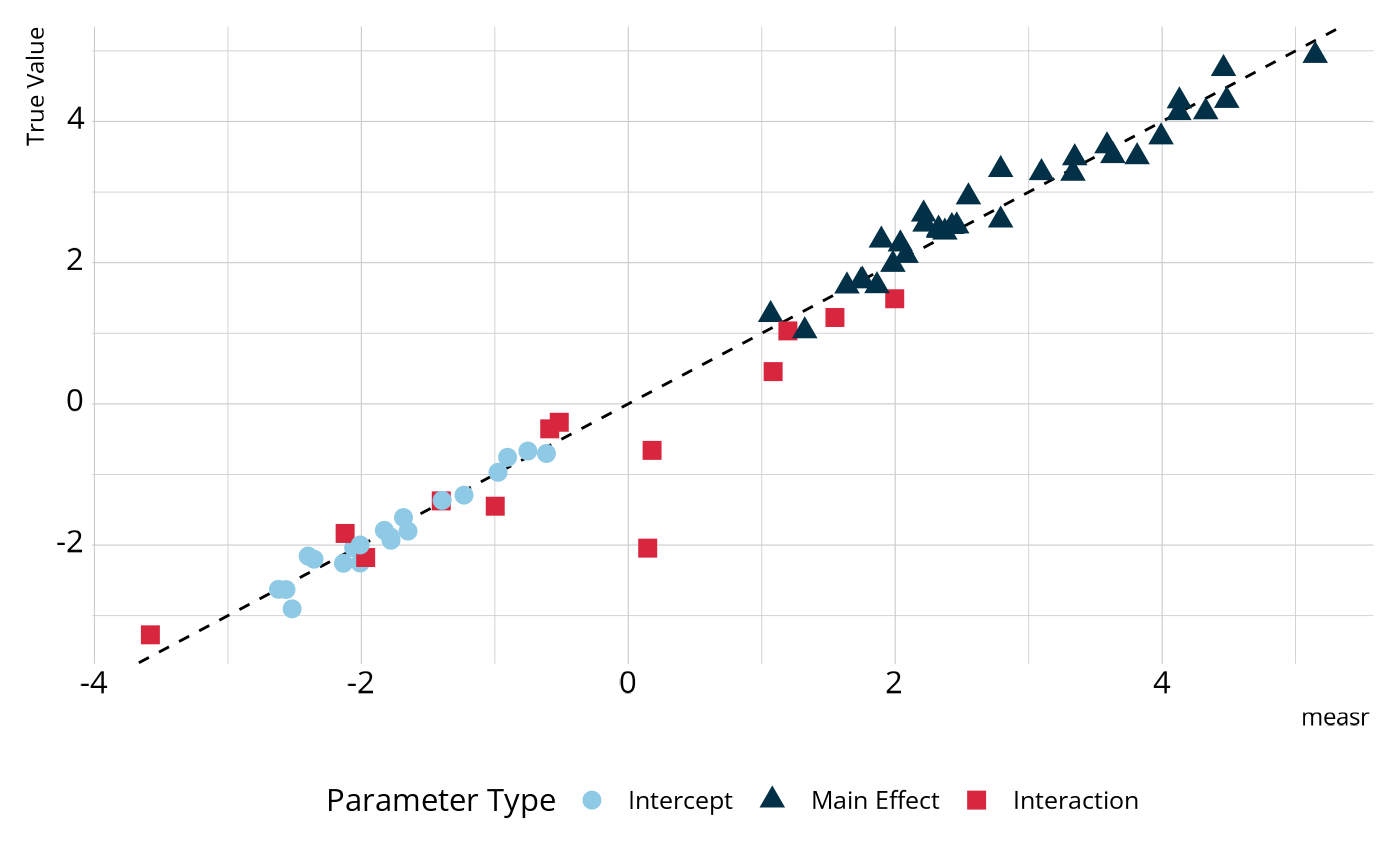

#> # ℹ 56 more rowsWe can compare these estimates to those that were used to generate the data. In the figure below, most parameters fall on or very close to the dashed line, which represents perfect agreement, indicating that the estimated model is accurately estimating the parameter values.

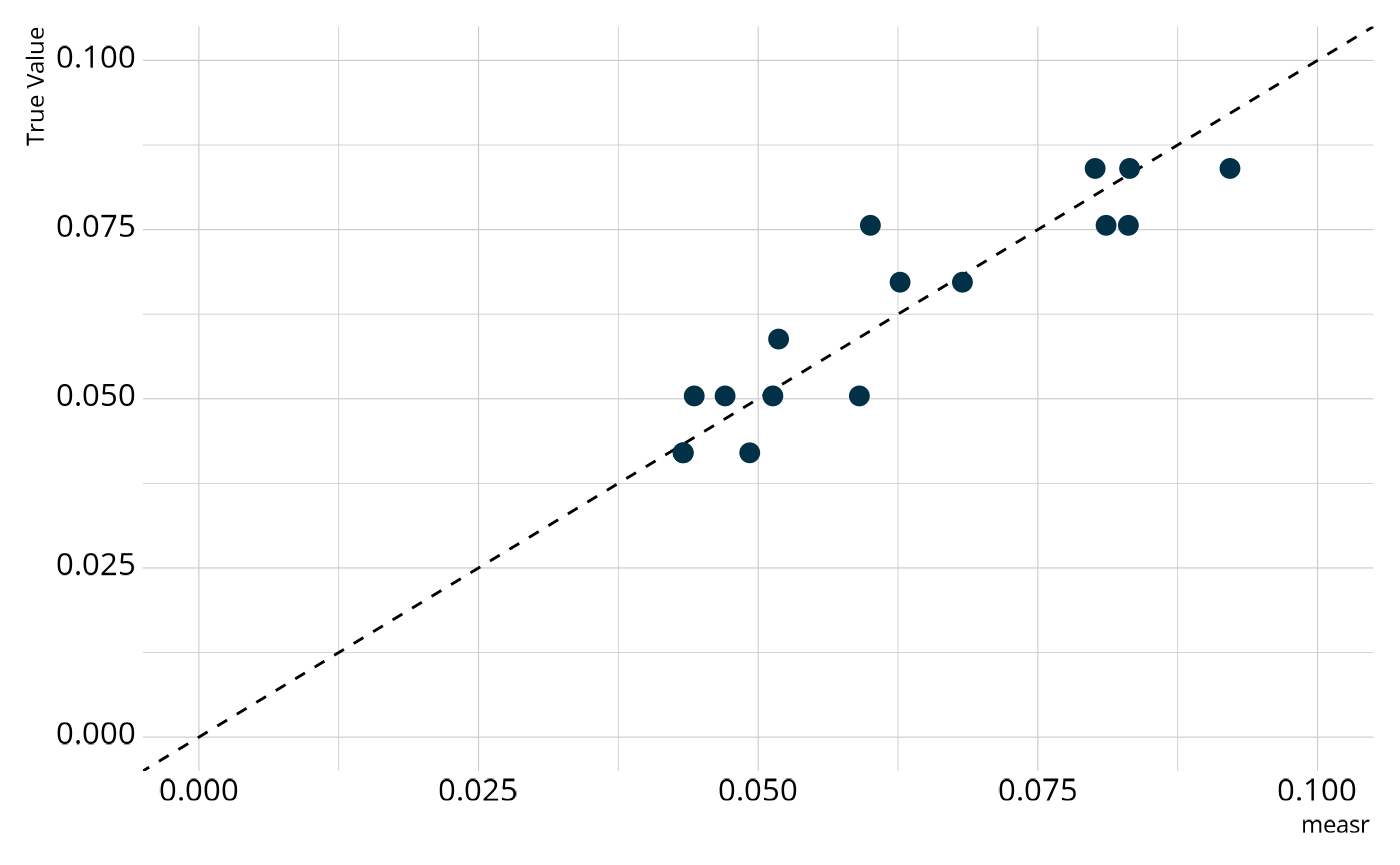

We can also examine the structural parameters, which represent the overall proportion of respondents in each class. Again, we see relatively strong agreement between the estimates from our model and the true generating values.

Customizing the Model Estimation Process

Prior Distributions

In the code to estimate the LCDM above, we did not specify any prior

distributions in the call to measr_dcm(). By default, measr

uses the following prior distributions for the LCDM:

default_dcm_priors(type = "lcdm")

#> # A tibble: 4 × 3

#> class coef prior_def

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 intercept NA normal(0, 2)

#> 2 maineffect NA lognormal(0, 1)

#> 3 interaction NA normal(0, 2)

#> 4 structural Vc dirichlet(rep_vector(1, C))As you can see, main effect parameters get a

lognormal(0, 1) prior by default. Different prior

distributions can be specified with the prior() function.

For example, we can specify a normal(0, 10) prior for the

main effects with:

prior(normal(0, 10), class = "maineffect")

#> # A tibble: 1 × 3

#> class coef prior_def

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 maineffect NA normal(0, 10)By default, the prior is applied to all parameters in the class

(i.e., all main effects). However, we can also apply a prior to a

specific parameter. For example, here we specify a χ2

distribution with 2 degrees of freedom as the default prior for main

effects, and an exponential distribution with a rate of 2 for the main

effect of attribute 1 on just item 7. To see all parameters (including

class and coef) that can be specified, we can

use get_parameters().

c(prior(chi_square(2), class = "maineffect"),

prior(exponential(2), class = "maineffect", coef = "l7_11"))

#> # A tibble: 2 × 3

#> class coef prior_def

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 maineffect NA chi_square(2)

#> 2 maineffect l7_11 exponential(2)

get_parameters(sim_data$q_matrix, item_id = "item_id", type = "lcdm")

#> # A tibble: 67 × 4

#> item_id class attributes coef

#> <fct> <chr> <chr> <glue>

#> 1 A1 intercept NA l1_0

#> 2 A1 maineffect att2 l1_12

#> 3 A1 maineffect att4 l1_14

#> 4 A1 interaction att2__att4 l1_224

#> 5 A2 intercept NA l2_0

#> 6 A2 maineffect att3 l2_13

#> 7 A2 maineffect att4 l2_14

#> 8 A2 interaction att3__att4 l2_234

#> 9 A3 intercept NA l3_0

#> 10 A3 maineffect att1 l3_11

#> # ℹ 57 more rowsAny distribution that is supported by the Stan language can

be used as a prior. A list of all distributions is available in the

Stan documentation, and are linked to from the

?prior() help page.

Priors can be defined before estimating the function, or created at

the same time the model is estimated. For example, both of the following

are equivalent. Here we set the prior for main effects to be a truncated

normal distribution with a lower bound of 0. This is done because the

main effects in the LCDM are constrained to be positive to ensure

monotonicity in the model. Additionally note that I’ve set

method = "optim". This means that we will estimate the

model using Stan’s optimizer, rather than using full Markov

Chain Monte Carlo. Note that the prior still influences the model when

using method = "optim", just as they do when using

method = "mcmc" (the default).

new_prior <- prior(normal(0, 15), class = "maineffect", lb = 0)

new_lcdm <- measr_dcm(data = sim_data$data, qmatrix = sim_data$q_matrix,

resp_id = "resp_id", item_id = "item_id",

type = "lcdm", method = "optim", backend = "cmdstanr",

prior = new_prior,

file = "fits/sim-lcdm-optim")

new_lcdm <- measr_dcm(data = sim_data$data, qmatrix = sim_data$q_matrix,

resp_id = "resp_id", item_id = "item_id",

type = "lcdm", method = "optim", backend = "cmdstanr",

prior = c(prior(normal(0, 15), class = "maineffect",

lb = 0)),

file = "fits/sim-lcdm-optim")The priors used to estimate the model are saved in the returned model

object, so we can always go back and see which priors were used if we

are unsure. We can see that for the new_lcdm model, our

specified normal prior was used for the main effects, but the default

priors were still applied to the parameters for which we did not

explicitly state a prior distribution.

measr_extract(new_lcdm, "prior")

#> # A tibble: 4 × 3

#> class coef prior_def

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 maineffect NA normal(0, 15)T[0,]

#> 2 intercept NA normal(0, 2)

#> 3 interaction NA normal(0, 2)

#> 4 structural Vc dirichlet(rep_vector(1, C))Other DCM Sub-Types

Although a primary motivation for measr is to provide researchers

with software that makes the LCDM readily accessible, a few other

popular DCM subtypes are also supported. For example, we can estimate

the deterministic inputs, noisy “and” gate (DINA,

Junker & Sijtsma, 2001) or the

deterministic inputs, noisy “or” gate (DINO, Templin & Henson, 2006) models by

specifying a different type in the measr_dcm()

function.

Future development work will continue to add functionality for more DCM subtypes. If there is a specific subtype you are interested in, or would like to see supported, please open an issue on the GitHub repository.